Claude Lambert's Magic Touch Brought European Animation to Life For Decades

From film posters to features, shorts and global tv series, the Belgian painter has been at the heart of Belgian animation for more than 50 years.

Even in Belgium, the name of Claude Lambert is little known outside the animation industry. But his art, on the other hand, has been seen by millions.

Who is this mysterious artist mostly forgotten by Belgian cinema history, who collaborated with both art house directors and big studios?

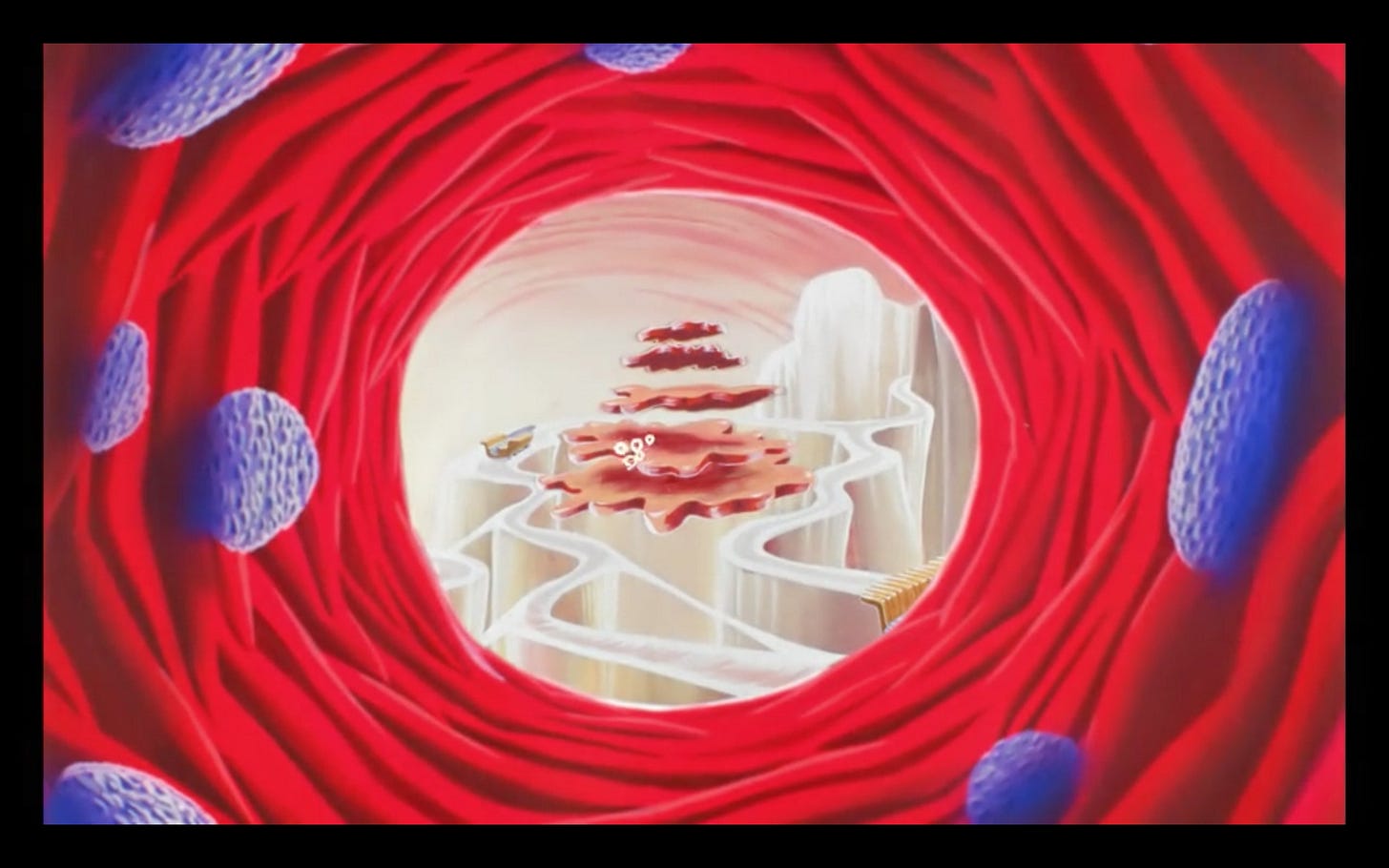

Here are a few examples of Claude Lambert’s work, try to guess from where those backgrounds come from.

By now, you may have guessed it, Claude Lambert has been part of major European projects such as Belvision hits Astérix et Cléopâtre, Tintin et le Lac aux requins, Lucky Luke’s Daisy Town, and is behind backgrounds of Albert Barillé’s franchise Once upon a time… [Man, Life, Explorers, …]

And as a young animation fan, these drawings shaped my whole world. So you can imagine how happy I was when he answered almost immediately to my interview request, thanking me for my proposition.

Lambert has been living in the quiet Spanish countryside for fifty years, but I managed to reach him by phone last week, and even though my recorder broke and messed up half of the interview, I’m delighted to be able to share it with you here today.

The beginnings

Claude, thank you for your time and your availability. Could you share how you started your journey into the animation industry?

After art school, I got hired to do film posters. At that time, film posters were created and painted for every movie, and so I moved to Brussels city center and worked in that sector for four years. I was in charge of the backgrounds, and my boss would paint the actors.

This was a very important part of my training, especially regarding speed of delivery. We worked for fourteen cinemas, so we had to be efficient, fast, and it helped me a lot when I started working for Belvision.

How was it, and how did it evolve during your different collaborations with the studio?

For my first feature collaboration at Belvision, Pinocchio in Outer Space [directed by Ray Goossens in 1965], we had a freedom to draw backgrounds and decors as I’d like. Unfortunately, working with other material later on, such as Asterix or Tintin allowed me less freedom because it had to match the style and shapes of the original work.

But the very important thing to keep in mind is that my work had to match the animation and allow the characters to move freely. So I always started from the rough pencil drawings, and build my backgrounds with these animation in mind. In that sense, it was close to what I did with the film posters, only I had to work even faster.

When I started, we were seven or eight background artists at Belvision, but they dropped out one by one because they couldn’t keep up the pace. I eventually ended up worked almost alone. Belvision hired me an assistant, we worked closely together and we ended up married each other, and I’ve worked with my wife ever since.

From long to short form

While you were working at Belvision, you also continued on other paths…

Indeed. Later in the 1970s, Picha [Belgian cartoonist and animation director Jean-Paul Walravens] reached out to me because he had seen my work, and he wanted me to do backgrounds for his upcoming feature Shame of the Jungle (1975). I only had time to do a few for this one, but I really enjoyed our collaboration and I went to work with him on Le chaînon manquant (B.C. Rock, 1980) and all his later projects, until his latest in 2007, Snow White: The Sequel. It was a great collaboration, which allowed me more artistic freedom than at Belvision.

Along with Picha, you also worked with Belgian director Gerald Frydman on his shorts?

With Gérald, we clicked almost instantly. He wanted for us to collaborate also, and as I had moved already to Northern Spain, he came to me and we discussed a lot his project which then became Agulana. He then went back to Belgium, created the film and won the Palme d’Or in 1976. For me, it’s one of his best shorts. After that, we collaborated on Le cheval de fer in 1984 and Les effaceurs in 1991. He’s an exceptional artist, and I love worked with him even though we had little funding for those films.

[You can discover more about Frydman’s films here]

Tv series and beyond

In the 1990s, you also started working with tv, how was the change for you?

The good thing was, I had way more freedom to express my creativity. Especially on Once Upon a Time… Life, which was liberating. As there was no references to match, it was way more interesting, and I think that’s the period of my life where I did my best work.

Painting also took a bigger part of your life?

With painting, there is no deadline, no rush. It allows me to keep using pencils, brushes and colors. This morning, I was in my workshop painting, and I love it. There is no stress, no pressure. I do exhibitions a lot, but without the same rhythm I had to keep up with in the animation industry.

From your experience and your decades-spanning career, would you have advice to young talents that want to start their journey in animation today?

I did not follow the latest trends in animation. I enjoy 3d, and I think there are good artists out there doing beautiful things with it, but I always remained faithful to traditional painting and animation.

What I find saddening is that there as been — at least in mainstream media — a drop of quality in the animation, and a uniformity that does not put the artists forward.

But there are still some great artists. I never was a good teacher, but what I would say is: nurture your talent, and keep close to the physicality of animation. Drawing, painting, it helps you go deeper into your art, and that’s key.

You can discover more about Claude Lambert’s art on his blog, or through his IMDb page.

For those familiar with the show, this opening may be the best way to pay an homage to Claude’s work. So feel free to dive back into this childhood memory here below.

In the meantime, I wish you a happy animated weekend.

Kevin